Cape Town’s Water Crisis

Posted on May 13, 2018

“Water is life’s mater and matrix, mother and medium. There is no life without water.”–Albert Szent-Gyorgyi

I took some time between assignments in South Africa recently to document Cape Town’s water crisis and was struck by what I found. Here one sees the cracked, dry bed of Theewaterskloof Dam–the largest dam in the South Africa’s Western Cape water supply system. The dam, which usually supplies Cape Town and its population of over 4 million people with 41% of its water, is now at critically low levels. Last year, Cape Town announced plans for “Day Zero”, when the municipal water supply would largely be shut off, potentially making Cape Town the first major city in the world to run out of water.

While “Day Zero” has now been pushed off till 2019, the water crisis is still dire and local residents are adapting their lives to deal with it. Below are some images capturing life in Cape Town and its outskirts during this unprecedented time period.

Capetonians line up with their water containers at the Newlands spring in a suburb of Cape Town. The spring, whose water is supplied by nearby Table Mountain, has flowed without interruption since record keeping started in South Africa, but has only recently becoming a critical collection point. Because of rising water costs and tight restrictions on municipal water usage, local residents come to the spring to fill up on the clean mountain water they use primarily for drinking and cooking.

Family outings to fill up on spring water are commonplace as collection is limited to 25 liters a visit so families may come to the spring as often as two to three times a week.

A woman washes clothing in a shallow bucket of water in Asanda Village–an informal shanty town settlement on the outskirts of Cape Town. Many of Cape Town’s poorer residents have pointed out that their communities–where residents don’t generally own washing machines, dishwashers and swimming pools–are not the ones using large amounts of water and yet are being penalized more than the wealthier communities where many residents have put in expensive boreholes (wells) and are thus skirting water restrictions.

A man walks across an empty public swimming pool–closed due to the water crisis–in the West Ridge district of Mitchell’s Plain on the outskirts of Cape Town.

Signs from a public relations campaign to decrease the University of Cape Town’s water usage are plastered on a university bulletin board.

A public protest in front of the parliament building on South Africa’s “Freedom Day” on April 27th this year included signs protesting the privatization of water. Ironically, Cape Town’s water crisis has been a boon to water privatization with the bottled water industry seeing huge growth in sales and private desalination plants setting up shop on the Western Cape’s shoreline.

As with any crisis, creative entrepreneurs have found ways of making some income from the city’s water crisis. Here, enterprising workers, for a fee, offer to transport heavy water containers from a public spring on Spring Road to residents’ waiting cars.

One of multiple private desalination plants sets up its temporary structure in Monwabisi on Cape Town’s False Bay. The plant, which was erected in a matter of months in reaction to the water crisis and is expected to produce seven million liters of drinkable water per day when it is complete, pulls water out of the ocean 1km out to sea near a popular pool and beach area.

Land of Color and Grace: A Visual Journey through Vietnam

Posted on April 9, 2018

What can I say in a few paragraphs about a country as beautiful, complex and mysterious as Vietnam? While many people’s first association with Vietnam may be that of the US/Vietnam conflict and all the horrifying and iconic imagery that accompanied it, what we discovered on our recent three week exploration of the country couldn’t be further from that.

Vietnam these days is a bustling, colorful, dynamic and geographically diverse country with a beauty, mystique and gentle quality all of its own. From the first day we arrived in Hanoi’s “Old Quarter” and were immediately greeted with fresh mango juice by our hotel’s friendly owner to the last part of our trip during which we cooked catfish Pho with our hosts on the banks of the Mekong Delta, we found Vietnam’s people to be disarmingly friendly and open. We were also consistently struck by the beauty of many of the places we visited–Halong Bay with its hundreds of limestone islands and blue waters, the cathedral-like chambers of Phong Nha’s extensive caves, the French colonial architecture and colorful lanterns of old world Hoi An, the lush green rice paddies on the outskirts of many towns and the dramatic coastal vistas of the Côn Đảo Islands. We were also seduced over and over again by Vietnam’s absolutely delicious food. Ginger, garlic, lemon grass, fresh herbs, interesting textures and creative combinations made every meal an exciting adventure and possibly one of my favorite countries food-wise.

And if this isn’t all enough to convince one to start dreaming up a trip to Vietnam, the country is also remarkably inexpensive to travel in. While many hostels, homestay and low-end hotels can be found for under $15, even the plusher hotels rarely go much over $40. For us this meant we could enjoy our journey, eat like kings, explore the

country on bicycles, paddle boards, motorcycles, boats and buses and embrace grand adventures we would perhaps not have been able to afford in a higher priced environment. The trip was beyond memorable and left us wanting to encourage others to replace their own associations of Vietnam with more positive and and current versions. On that note, I leave you with one of my favorite travel quotes and some of the images I created along the way:

“Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all of one’s lifetime.” – Mark Twain

A quiet Sunday morning in the beautiful town of Hoi An.

Paddle boarding in Halong Bay.

Paddle boarding in Halong Bay.

I photographed Thanh Nhàn– surrounded by the paper lanterns she sells at one of the tourists craft shops– at “the Citadel”, an archeological site in Hue. Thanh told me her passion is to make paper flowers and for each of her creations, she writes an accompanying poem. I was struck by her sweetness, by the beauty of the flowers and poems she creates and by her determination to soon open her own shop selling her flowers and poems.

A sweet and colorful moment I captured while bicycling in the rain through a very quiet village near Phong Nha.

I photographed these two young women surrounded by Hanoi’s colorful cherry blossoms in Hoan Kiem Lake Park.

A woman sells bananas on the side of the road while motorcyclists sit stuck in the glut of motorcycle traffic in Hue. I was struck by the massive number of motorcycles ones sees in Vietnam–one of my least favorite aspects of the country–and the constant honk of horns that accompanies them.

A group of Vietnamese women play a card game in downtown Hue.

A woman bicycles through a village in the Mekong Delta Region.

A woman reacts joyfully to seeing a friend while wearing traditional clothing at the Imperial “Citadel”–the one time home of Vietnam’s Nguyen Dynasty–in Hue.

School boys ride their bicycles through the chaos of pedestrian and bicycle traffic in Hoi An.

Just a few of the many lanterns that light up the town of Hoi An–a UNESCO Heritage Site filled with beautiful French Colonial architecture on the banks of the Thu Bon River.

A cat and dog communally observe the world from their home in Hoi An.

Fishermen are illuminated in the morning sun while fishing in the Thu Bon River in Hoi An.

Young men use a net to fish in a canal beween the rice paddies in Hoi An.

A colorfully dressed woman sells bananas at the local market in Hoi An.

Fishermen return their boats to port after a day of fishing in Con Son Bay in the beautiful and mysterious Côn Đảo Islands.

One of the many house boats from which people sell wholesale fruit, agricultural products and specialties at Cai Rang floating Market in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta region. During early morning hours, the waterway becomes a maze of boats packed with goods and food.

A man purchases watermelons from a wholesaler at Cai Rang floating Market in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta Region.

A beautiful young woman is photographed in the traditional Vietnamese hat which is kept on the head by a cloth (often silk) chin strap. Vietnamese women are very conscious of protecting their skin from the sun as paler skin denotes higher social status and indicates the fact that the woman doesn’t have to work in the fields so many women not only wear a hat but also use a cloth to cover much of their face.

I was struck by this man napping in a rather uncomfortable-looking position outside a barbershop–despite the loud honking of horns and general city noise–in the bustling city of Can Tho in the Mekong Delta.

Snakes and other creatures sit in a vat of “snake rice wine”–slowly flavoring the concoction in the Mekong Delta region. Along with snake rice wine, we encountered exotic Vietnamese dishes featuring crickets, ant eggs, cobra, crocodile and rat. While these particular dishes may not appeal to Western tourists, Vietnamese food in general is incredibly delicious, full of fresh herbs and spices and rich in flavor.

A scene from the night food market in Can Tho in the Mekong Delta region. Street food is exceptionally cheap in Vietnam so many locals purchase their evening meal (often for under a dollar) at one of the night markets.

One of those sublime moments of travel on Con Dao Island.

Mujeres de la Habana: an intimate look at the lives of modern Cuban women

Posted on September 4, 2017

The Cuban Revolution affected women’s lives and gender relations dramatically and on paper, it offered them equality and gave them access to more channels of political and social power. But what is the reality of women’s lives in Cuba today? Having long explored issues of female identity and experience in my work as a photographer, I was interested in looking at the lives of modern Cuban women and finding out what their experiences were in Cuba’s current post-revolutionary political and social climate. The portrait series that emerged–which was shot solely with a Leica camera and includes in-depth interviews with each of the women–is an intimate look at the struggles, perceptions, hopes and dreams of its subjects.

Delsa Pena, 85, lives alone in a small dark apartment in Havana and spends her days walking around the city so that she doesn’t feel too lonely. She has six children, 14 grandchildren, 16 great grandchildren and one great-great grandchild. “The hardest experience in my life was when my husband fell in love with another woman and I had to leave him,” she says. “I’ve always been unlucky in love,” she adds. Of Cuban women she says, “we are beautiful loving and respectful. Before the revolution, we were domestic servants but now we have more rights and possibilities.”

Grether Ballaga Perez, 25, plays the cello for the orchestra of the Grand Havana Theater of Cuba. She studied music at the prestigious “Instituto Superior de Arte” and dreams of playing for an orchestra outside of Cuba. “The hardest thing in my life was when my father disappeared when I was 15 year old. Everything in my life changed after that and we still don’t know where he is. He worked on a cargo ship so we think maybe he’s in Europe with another family.” Of Cuban women, she says “a Cuban woman can become what she wants to be in this culture. I believe we have the same rights as men and are prepared to face any system, any society.”

Arletis Francis, 26, photographed here at one of Havana’s beloved salsa clubs, grew up in Guantanamo and came to Havana to study engineering. “I was so sad to leave my family but I knew I had to come here if I wanted to study,” she says. She currently teaches computer skills to high school students and teaches salsa dancing on the side. “My dream is to become a professional salsa dancer but is it very difficult. You have to get special papers to get the jobs that pay well, she explains. “Actually, even now I make less as a computer teacher than a dancer and I also love to dance,” she adds. Of Cuban women, she says “we are strong, fight hard, wake up every day to solve our family’s problems and we are resilient.”

Semara Garcia Gutierrez, 43, is currently serving a three year prison sentence in Matanzas but was photographed while on weekend leave visiting her mother in Old Havana. “I took the fall for a friend during a street knife fight,” she explains. “Prison conditions aren’t too bad.There are problems with food and water but everyone has their own bed and the guards are usually kind,” she says. She is enrolled in a cooking course in the prison and dreams of one day sharing a home with her female partner and working as a chef. “Homosexuality is not accepted here in Cuba but people are becoming more open,” she says. “My mother and grandmother have always accepted me,” she adds. Of Cuban women she says “we are strong, beautiful and able to face anything because we’ve gone through so much already.”

Caridad Miranda, 53, photographed in her home with some of her family members and the laundry from her youngest grandchildren, lives with her husband, eight children and eight grandchildren. She studied theater at the prestigious “Instituto Superior de Arte” and has been a singer and actor, even performing in several Cuban movies. “The hardest thing in my life right now is our housing situation because there are just too many people living here and not enough food. We gets food rations but it’s not enough for all of us.” Of Cuban women, she says “being a Cuban woman means being everything for one’s family.”

Artist and photographer, Ismary Gonzalez Cabrera, 48, is photographed in her studio in Old Havana. “My parents were devoted to the revolution and were quite absent so I had a lonely childhood,” she says. She has one child, Pablo, and tries to share her experiences through her art. “I’m so happy that I have been able to make art my career. I know many artists struggle to live off their art and to me it is my greatest achievement,” she adds. She dreams of traveling to other countries and experiencing other cultures but knows that isn’t realistic at the moment. Of Cuban women, she says, “We are warriors. Like everyone, we need love, we need family and we need work.”

Meivys Sahily Guilarte Miranda, 35, is a musician specializing in percussion and voice. She studied music for six years before getting a contract to play percussion in Singapore and then later moved to Bali to play Top 40 music. “The culture was so different in these places but I lived with Cubans so that made it easier,” she explains. She recently returned to Havana to look after her sick mother and reestablish her career there. “It was a triumph to come home after so long,” she says. “If I could make it over there, I think I can make it here,” she adds. Of Cuban women she says “we are very expressive. We show what we feel…and we love to dance!”

Yarlenys Torres, 34, is photographed in the hallway of her building where she dries laundry. She lives with her husband and two children in an apartment that doubles as her husband’s tattoo parlor. While she completed a basic computer course after high school and also sings and writes, she’s happy being a mother and wife at the moment. “I have everything I want–a family, a home, love,” she says. “I dream of traveling to Brazil one day because I thing my grandfather was from there and I would love to experience it.” Of Cuban women, she says “we are social, loving and communicative. We keep the family together.”

Ismaela Perez, 76, is photographed in her home in Havana. She came to Havana the year of the revolution and became involved in a social organization teaching literacy. During the missile cirsis, she was mobilized with a group of women in a leadership role in the mountains. “We were totally isolated and had no idea what was happening with the crisis. We got a lot of distorted news and didn’t know if the war or the world had ended,” she explains. While she married, she couldn’t have children. I was sad that I couldn’t have children but in every student, I saw a child that I could nurture and I always felt my career was fulfilling,” she says. “Cuban women are brave and show solidarity between each other and women in other countries. I think Cuban women face many difficulties but remain stoic,” she adds.

Gabriela Fernandez, 17, who was moving to the United States a few days after this photograph was taken, is photographed in her bedroom with the suitcase and few possessions she is taking with her to the US. She was raised primarily by her mother, with whom she is very close, who gave birth to her at age 17. Her mother recently married a man from the United States which is why they are moving to the US. “We’re not the revolutionary generation and we haven’t seen the good part of the revolution,” she says. “Everything in this country is controlled by the government and the media especially is so restricted which my generation of course does not agree with,” she explains. “Cuba has good things too though. We have a lot of free time and young people have fun because there’s not so much pressure on us. But if you want to do something big with your life, it’s hard,” she adds. Of Cuban women, she says, “to be a Cuban woman is to be self-critical, intelligent and passionate. Every woman in this country has had to sacrifice their whole lives.”

Lions, Leopards and other Wild Longings

Posted on February 13, 2017

A leopard peeks through the trees in the Masai Mara National Park in Kenya. This extraordinary close encounter was just one of many moments in my life that has fueled my passion for being in the wilderness and for capturing a world that remains as mysterious and beautiful to me as ever.

[su_spacer]

“Nature has been for me, for as long as I remember, a source of solace, inspiration, adventure, and delight; a home, a teacher, a companion.”— Lorraine Anderson

Having spent my childhood in South Africa, I began an early love affair with the wilderness. Some of my most vivid memories are of lying awake at night listening to the roar of lions accompanied by a string quartet of cicadas, imagining the secret nighttime rituals happening outside in the dark.

A beautiful male lion I photographed in the Masai Mara. In the wild, males seldom live longer than 10 to 14 years as injuries sustained from continual fighting with rival males greatly reduce their longevity. Although this lion is relatively young, one can already see the scarring on his face from the various fights he has had.

A two month-old lion cub looks up at two lionesses. Lionesses raise their cubs communally and cubs suckle indiscriminately from any lactating female.

A lioness feeds on a freshly-killed zebra carcass. Lionesses are the hunters in the pride and co-ordinate with each other to surround their prey and stalk them before sprinting in a short burst, finally killing them by strangulation. They then share the weight of the kill on the journey back to the group where all the lions eat.

A leopard relaxes in a tree after eating part of a kill which he hung on a nearby branch. Leopards store their kills in trees to prevent other predators from stealing them.

Elephant calves share a playful moment using their trunks in Amboselli National Park. At first, baby elephants don’t really know what to do with their trunks. They swing them to and fro and sometimes even step on them. They will suck their trunk just as a baby would suck its thumb. By about 6 to 8 months, they begin learning to use their trunk to eat and drink. By the time they are a year old, they can control their trunks relatively well.

An elephant grazes in Amboseli National Park in Kenya. Elephants are extremely intelligent animals and have memories that span many years. It is this memory that serves matriarchs well during dry seasons when they need to guide their herds, sometimes for tens of miles, to watering holes that they remember from the past. They also display signs of grief, joy, anger and play.

A cheetah mother and her cub relax under a tree during the heat of the day. On average, a female cheetah will give birth to three young at once but even under a mother’s watch, 90 percent of cubs die before they are three months old. Considered the world’s fastest land mammal, a sprinting cheetah can reach up to 64 mph.

A lilac-breasted roller perches on a stick from where it can spot insects, lizards, scorpions, snails, small birds and rodents moving about at ground level.

A vervet monkey and her few day-old infant warm up in the morning sun in Amboseli National Park. In groups of vervet monkeys, infants receive a tremendous amount of attention. Days after an infant is born, every member of the group will inspect the infant at least once by touching or sniffing.

A masai giraffe grazes on a tree in the Masai Mara. Masai Giraffes mainly feed off whistling-thorn acacia trees, using their long lips and tongues to reach between the thorns to extract the leaves.

A secretary bird is photographed in Amboseli National Park. Like most birds, secretary birds spend their lives in monogamous pairs. During courtship, they soar high in the air with undulating flight patterns and call out to each other with guttural croaking. Males and females can also perform a grounded display by chasing each other with their wings up and back, much like the way they chase prey.

A zebra suckles her foal in Amboseli National Park. Baby zebras can begin running about one hour after they are born.

Adult spotted hyenas and their week-old cubs are photographed near their den in the Masai Mara. Besides flesh, hyenas eat skin, bones, and even animal droppings. Surprisingly, hyenas are not related to dogs even though they look similar and have similar greeting ceremonies.

[su_spacer]

My blog–Apertures and Anecdotes–strives to be an interesting place of discovery–a place to share beautiful photos, discover new places and people and lose oneself in this extraordinary medium. If you or someone you know would like to receive new blog posts directly through your email, please sign up directly on my blog site–Apertures and Anecdotes (in the right hand column)–or email me at julia@juliacumesphoto.com. Thank you!

ps. comments are closed due to an overabundance of spam but please feel free to respond to this blog post directly if you have any questions or comments.

Images from Another World: The Samburu Women’s Photography Workshop

Posted on April 14, 2016

Some of my Samburu workshop women practice photographing after their first training session. The women are members of a women’s empowerment group–the On’gan Women’s Cooperative–which was formed in 2008 and brings women together in collaboration to start they own initiatives and is generally a community resource to build self-determination and autonomy.

On the first day of the Samburu Women’s Photography Workshop in Kenya a few weeks ago, I was greeted by the wonderful sight of my workshop attendees singing and clapping their hands as they slowly processed into Sabache Camp—a community owned and run camp—where the workshop was to be held. Adorned in their colorful clothing and intricately crafted beadwork, their beautiful voices rose up and mingled with the sounds of birds, cicadas and other small wildlife in the bush around us. It was a joyful moment for me and was somehow a fitting start to this unusual adventure for us all.

I’d come to this wildlife-rich and remote part of Kenya to teach a photography workshop to a women’s empowerment group–The On’gan Women’s Cooperative–made up of tribal Samburu women. The group was formed in 2008 and brings women together in collaboration to start their own initiatives or businesses and includes micro finance programs, vocational training programs and is generally a community resource to build self-determination and autonomy. While I’ve taught photography to children in Rwanda over the last two winters and have spent quite a bit of time in East Africa, I knew little about the Samburu tribe or how these women might respond to the workshop.

The photo workshop was a collaboration between myself and a local college professor/lead lion researcher at the Lion Conservation Fund, who has been working closely with the Samburu community for years. She had told me about the women’s empowerment group and together we’d come up with the idea of the workshop which she then presented to the community, the cooperative and the tribal elders.

After their approval and with the help of a local Cape Cod photography shop, Orleans Camera, who donated nine point and shoot digital cameras, as well as funds from the sale of prints and calendars at my recent “Uncommon Journeys” photography show and a few other private camera donations, I arrived in Kenya ready to share my enthusiasm for photography with women who had never even seen a television before. I had also brought with me a small printer so that we could make prints of the women’s work for them to take home with them and for a community board where others could see the prints.

Having worked with children in Rwanda at the Through the Eyes of Hope Project, I had first hand knowledge of how empowering and joyful photography could be. There was also the thought that the photography workshop could help document the Samburu women’s lives and stories and elevate their voices. As ancient cultures change and rapidly disappear across the globe due to globalization and development, these stories and images could be instrumental in helping them document and record their culture and traditions from their own perspective before they are lost forever. Most importantly, I hoped this would be a fun, empowering and useful experience for the women.

The Samburus, who live in the Rift Valley Province of Northern Kenya, are closely related to the Masai tribe and are semi-nomadic pastoralists which is one of the reasons they’ve been targeted. They live in small clusters of homes called “bomas” made of mud, hides and grass mats strung over poles. Cattle, sheep, goats and camels are central to their way of life and their diet is made up primarily of milk as well as roots, vegetables, tubers and some blood from livestock. Since the Samburu tribe has been relatively isolated from western culture, despite the pressure to settle into more permanent settlements, their culture remains quite intact and they live very much as they have for generations—another reason they’ve been targeted by external groups who see them as “culturally backward”.

Over the days that followed my arrival, the women learned to use the cameras, looked at many images on my computer as I presented ideas about composition, light, creating portraits, capturing “moments” etc. and had a great time photographing everything in their path. Women’s empowerment group coordinator and translator, Naomi, translated our back and forth communications and I was immediately struck by the women’s sense of humor, their openness and their connection to each other.

I knew that many of the women had had the experience of being photographed by tourists but had never had the opportunity to capture their own lives. Now they joked over and over how they were “Mzungus” (white people) and a few even hatched a plan to whip out their cameras next time a safari vehicle pulled up beside them with a bunch of tourists eager to photograph them.

When they returned to their villages, I asked them to photograph the things that were important in their lives and a few days later when they came back, I was enthralled with the worlds I saw unfolding as I edited their images. Their homes, their children, goats, camels, beautiful Mount Ololokwe—it was clear to me that they had fully embraced their assignment and had lovingly captured the world that was so familiar and meaningful to them.

I was touched by the fact that some of the women had even made special pouches in their skirts to hold their cameras so they would have them close at hand. After editing images, each woman chose a few to take with her and I posted many others on the community board. I relished watching as not just the women but the men and others who had not been part of the workshop, joyfully looked at the photos together.

When it was time for me to leave, my only regret was that I didn’t have enough cameras to leave behind for all the women who had come to participate in the workshop. I promised myself that I would be back with cameras for those I didn’t have enough for this time around. Below is just a small selection of images from the workshop. Thanks so much to all the people who helped make this workshop happen and enjoy the photos!

Me with some of the Samburu elders who participated in the workshop. The Samburu culture reveres its elders and I noticed how it was the elders who spoke first and most confidently, who got first dibs on the cameras and had their work edited and printed before the younger women.

Maria, one of the most enthusiastic of the elder women, proudly dons her camera during the workshop.

Mampayun practices using her camera. I knew that many of the women had had the experience of being photographed by tourists but had never had the opportunity to capture their own lives from their perspective. Now they joked over and over how they were “Mzungus (white people) and a few even hatched a plan to whip out their cameras next time a safari vehicle pulled up beside them with a bunch of tourists eager to photograph them.

I really love this portrait of Samburu warrior, Lawrence, which was shot by workshop attendee, Siyale. Just a beautiful portrait with good composition and lovely light.

I thought this image, shot by Mampayun, beautifully captured a slice of village life and the centrality of livestock in Samburu culture. In the background, one can see Mount Ololokwe, a mountain considered sacred by the community.

A portrait Mampayun made of her niece in their village. This image not only shows the beads that all young Samburu girls but also how central camels are in the culture–something few people might know. One of my hopes for this workshop was that it would allow the women to capture their culture and traditions from their own perspective before they disappear and images like this I thought really did that effectively.

A portrait taken at the entrance of her “boma”–a traditional Samburu home made out of mud, hides and grass mats strung over pole– by Generica.

I thought this image, shot by Karini, captured the sense of connection and closeness between the workshop women. Just a sweet, candid moment.

This is one of my favorite candid moments Maria shot during the first day of our workshop. So rare that I’m on that side of the lens and she definitely captured the joy I felt learning how to dance Samburu style!

During the editing process, we looked at each of the women’s images and the women got to choose which images they wanted prints of to take home with them. Bottom far right is empowerment group coordinator and translator extraordinaire, Naomi, who really made communication with the women so easy. This photograph was shot by Sabache visitor, Christine Forster.

On the last day of the workshop, the women delighted in the prints posted for the community to see. So wonderful to see their joyful reaction to the prints of their work!

If anyone has a used point and shoot digital camera they no longer use, please send me an email at juliacumesphoto@gmail.com. Thank you!

This blog strives to be an interesting place of discovery–a place to share beautiful photos, discover new places and people and lose oneself in this extraordinary medium. If you or someone you know would like to receive new blog posts directly through your email, please sign up directly on my blog site–Apertures and Anecdotes (in the right hand column)–or email me at juliacumesphoto@gmail.com. Thank you!

ps. comments are closed due to an overabundance of spam but please feel free to respond to this blog post directly if you have any questions or comments.

Sublime Waters: A Journey Around New Zealand’s Dramatic South Island

Posted on February 23, 2016

Mark paddle boarding in New Zealand’s Marlborough Sounds–so perfectly described as “sea-drowned valleys”. Our paddle boarding experience here included gliding over large winged stingrays and thousands of jellyfish.

From the first day of our adventure traveling up the east coast of New Zealand’s South Island along the stunning rocky coastline, through a few sparsely populated little towns and copious fields of sheep, I knew this journey would challenge my usual photographic instincts. As a photojournalist whose work is generally centered on people and wildlife, photographing in such a sparsely populated place was at first a radical and sometimes uncomfortable departure for me. After a few days, I stopped looking for humans and began seeing what South Island offered up on another more sublime plane.

From our first few days in the Marlborough Sounds—described as a network of “sea-drowned valleys”—where we spent a surreal morning paddle boarding over large winged stingrays and thousands of jellyfish—I felt like we’d entered a magical new realm best described in shades of blue. I noticed how the water constantly shifted hue and texture as the island’s weather patterns rearranged light and wind.

Everywhere we went, the intersection between weather and water seemed to play out in a complex dance. In the North, Abel Tasman National Park offered up golden beaches, azure lagoons and long tidal flats that appeared mirage-like with their ribbons of color and occasional horse riders. In contrast, on the west coast, the waters were turbulent and unbridled, wearing the rocks into strange pancake formations and pounding the shoreline incessantly.

We spent an evening bicycling around the coastal town of Greymouth—once a bustling port for coal export that now seems a bit lost in time—stunned by the purplish evening hues and a whole new pigment we didn’t know water could acquire.

And then, further down the coast, there were the ice-blue glaciers rising up so unexpectedly after we emerged from rainforest. How can one make sense of a place so raw and elemental and seemingly connected to a geological past few of us understand?

And just when I thought the incarnations of water couldn’t get more dramatic, we spent an evening kayaking in pouring rain through Millford Sound’s interior bays surrounded by sheer rock faces that rise up 4,000 feet with thousands of waterfalls streaming down. Milford Sound—which is actually a fiord created by glacial erosion—was its own mythical country, full of rich Maori tales, dramatic tree avalanches and more rain than most of us can imagine standing.

Rounding the bend to South Island’s Catlins, we discover the rich marine life I’d been hoping to see and photograph. At Curio Bay—known to be a nursery for young dolphins—we watched these playful marine mammals surf waves and spring out of the water with seeming limitless enthusiasm.

At nearby Waipapa Point, a a harem of sea lions lay about in fat, happy arrangements, the large male occasionally rising to fend off a curious male challenger. Further up the coast, the ocean offered up the extremely rare and endangered yellow-eyed penguins. In the evenings, they’d be spat back onto shore after a day of fishing only to be accosted by their hungry chicks—mouth open, squawking, begging for food. Nearby, seal pups frolicked on the beach like energetic puppies while oyster catchers stabbed hungrily at shellfish.

Even heading inland to the interior lake region, I was struck by the unusual watery sightings like Lake Wanaka’s lonesome tree growing quite unexpectedly out of the water and the exquisite hue of Lake Tekapo, the turquoise blue of the Greek Isles. Apparently this remarkable color is the product of glacial sediment turned into fine dust particles suspended in water whose interaction with light creates the unusually bright blue hue.

And of course, beyond New Zealand’s sublime waters there is so much more—rainforests so green and moss-laden, the vast, raw Southern Alps, volcanoes, geysers and rollings greens pocked with sheep and cows. With the limitation of this blog post, I cannot begin to do justice to these beautiful places but in the meantime, here is my photographic experience of this rather unpeopled, transcendent place.

Riders walk their horses across one of Abel Tasman’s beaches at low tide. The park is known for its spectacular tidal estuaries and azure lagoons.

Looking down on one of Abel Tasman National Park’s exquisite lagoons from the park’s famous coastal hiking trail.

Early morning paddle boarders explore Tasman Bay–best described in shades of blue–in the sweet coastal town of Nelson.

The west coast’s waters, turbulent and unbridled, have worn limestone rocks into strange formations like a pile of pancakes, appropriately nicknamed “Pancake Rocks”.

Looking out of a an ocean cave–accessible only at lowtide– onto one of South Island’s more protected west coast beaches.

A brightly colored reef starfish hunts down its favorite prey–mussels–on South Island’s rocky west coast. The starfish plays an important role in reducing the expansion of invasive mussel species on the island.

Franz Josef’s ice-blue glacial face rises up out of steel-grey rock–a scene so unexpected after one emerges from the nearby rainforest hike.

Just when I thought the incarnations of New Zealand’s water couldn’t get more dramatic, we spent an evening kayaking in pouring rain through Millford Sound’s interior bays surrounded by sheer rock faces that rise up 4,000 feet with thousands of waterfalls streaming down.

At Curio Bay—known to be a nursery for young dolphins—we watched these playful marine mammals surf waves and spring out of the water with seeming limitless enthusiasm.

One of my favorite moments in New Zealand was photographing yellow-eyed penguins, the rarest penguins in the world. It was fascinating watching these penguin parents find a moment of reprieve from their penguin chick (on left) after it harassed them–mouth open, squawking, begging for food–as soon as they returned from their day of fishing. They did soon relent and feed it by regurgitating some fish.

An expressive moment between two sea lions at Waipapa Point. The male sea lion on the left had earlier chased off a challenging male and had now come to assert his prowess with one of his harem members.

A bleary-eyed fur seal poses on a cliffside at Katika Point on New Zealand’s wildlife-rich east coast.

Awed by Lake Tekapo’s remarkable color, I learned that it’s a product of glacial sediment turned into fine dust particles which are suspended in water. When light and the blue of the sky reflect off these particles, it creates the unusually bright blue hue.

This blog strives to be an interesting place of discovery–a place to share beautiful or disturbing photos, discover new places and people and lose oneself in this extraordinary medium. If you or someone you know would like to receive new blog posts directly through your email, please sign up directly on my blog site–Apertures and Anecdotes (in the right hand column)–or email me at julia@juliacumesphoto.com. Thank you!

ps. comments are closed due to an overabundance of spam but please feel free to respond to this blog post directly if you have any questions or comments.

98.7 % Human

Posted on April 6, 2015

Rescued chimpanzee, Eddy, is one of the many chimps I photographed for the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) at the Ngamba Island Chimpanzee Sanctuary in Uganda recently. Eddy was confiscated from Akefs Egyptian Circus in Kampala, Uganda in 1998 and arrived at the sanctuary very depressed. He has since done much better although he still sometimes shows signs of trauma and acts up.

Ngamba Island Chimpanzee Sanctuary is located on a magical little island in Lake Victoria, Uganda, and is home to 48 orphaned chimps rescued from Uganda and neighboring African countries. At the end of a month teaching photography to kids in Rwanda, I had the wonderful opportunity to spend four days on the island. I was there on assignment to document the chimpanzee sanctuary for the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), one of the sanctuary’s founders and continuing supporters.

When I first stepped off the small boat that brought me the 45 mins from Entebbe, I was struck by the intense chirping of birds. I soon discovered that the island is not only home to the chimps but to literally thousand of weaver birds as well as egrets, monitor lizards, fruit bats, otters, fish eagles and a variety of other small creatures. The island also houses an exceptionally caring staff who feed the chimps, clean the compound, educate visitors about the sanctuary’s work and generally ensure the chimps’ wellbeing. Innocent Ampeire, one of Ngamba’s most experienced caregivers, was the first staff member to welcome me and, wearing a shirt that read “98.7 % chimp”, proceeded to introduce me to the extraordinary microcosm that is Ngamba Island. With the birds singing, the chimps calling and hooting in the distance and the beauty of Lake Victoria all around me, I felt like I’d stumbled upon a little piece of paradise.

The Ngamba Island Chimpanzee Sanctuary was founded in 1998 with the idea that it could serve as a home for confiscated chimps who could not be returned to the wild. The island is about 100 acres, 98 of which are forested. Of the remaining two acres, one acre is used as camp quarters for staff and researchers and the remaining area, located between the forest and the viewing platform, is where the chimpanzees are fed during the day. While the chimpanzees spend the majority of their day in the forest, they do voluntarily return to the feeding area several times a day to eat as the forest’s natural food resources are not enough to sustain a group of that many chimps. Most of the chimpanzees also return at night through a long caged corridor to eat their evening meal and sleep in enclosures where they use straw to make a bed on their own personal hammocks.

In advance of my arrival on Ngamba, I did a little research about chimps to better understand what I would be photographing. I was immediately struck by the fact that we share 98.7 percent of our genetic material with chimpanzees. Like us, they have complex emotional and social worlds and even have different cultures depending on the region they live in. They experience joy, anger, grief, sorrow, pleasure, boredom and depression and also comfort one another by kissing and embracing. As Jane Goodall discovered during her well-known study of chimps in the 1960’s, chimps use tools such as stones to crack nuts, twigs to probe for honey or ants and even spears to hunt small animals! Their gestation period is very similar to humans, their body temperature is the same, they have opposable thumbs on their hands (and on their feet!) and, like humans, eat a variety of vegetables, leaves, fruit and animal protein. They enter adulthood at around 13 years old and, like us, share life-long bonds with their children. The primary difference between chimps and humans is that they don’t have language although they do communicate using a complex system of of sounds, facial expressions, gestures and body language.

As I spent time observing and photographing Ngamba’s chimps and learning about their personal histories over the days that followed, I became fascinated with how different they all were from each other, not just physically but emotionally. Innocent and the other caregivers know the chimps intimately and speak of them almost as familiar friends. They’d say things like “Medina seems depressed today” or “did you see how one of the others tried to steal Baron’s security blanket?” and then a discussion of the given chimp would ensue. They also make detailed notes in logs books about the chimps’ behavior and activity at the end of each day. I found these snippets of conversation about the chimps compelling and began to read and ask questions about each chimp’s personal story.

As I mentioned earlier, like humans, chimpanzees have close familial relationships so early separation from a mother–as most of the Ngamba chimps experienced–leaves deep emotional scars. Some of the stories I heard simply broke my heart. For example, Baron, who found a rag in the forest and holds onto it as a security blanket, was taken from his mother and kept in a wooden cage for a year along with sibling who died. Another chimp, Ndyakira, was confiscated as an infant from illegal wildlife traders in Uganda. She had been sent first to Russia and then to Uganda where the dealers were intercepted and she was found malnourished and traumatized. When female chimp, Medina, arrived at Ngamba Island, her canine teeth had been removed and her front teeth smashed. She was malnourished with a bloated stomach and was believed to have worms. She was treated and recovered steadily and is now a friendly and generous chimp. These are just a few of the painful stories I learned about during my stay.

While many of Ngamba’s chimps struggled to integrate, showed signs of depression or had behavior issues when they first came to the island, almost all have since managed to adapt and seem to be thriving. Hearing their stories and seeing what a rich and full life they now have on the island made me realize how special the sanctuary is and how important it is to have places like it in the world. With chimpanzee populations threatened by habitat loss, hunting and disease, there are few places where our closest relative can live peacefully and I feel honored to have spent time capturing this exceptional little spot on earth.

A chimpanzee sits in the crook of a tree in Ngamba Island’s dense forest. The island is about 100 acres, 98 of which are forested.

Female chimp, Ndyakira, was confiscated as an infant from illegal wildlife traders in Uganda. She had been sent first to Russia and then to Uganda where the dealers were intercepted and she was found malnourished and traumatized. After some time at the sanctuary, she happily integrated into the group and loves being in the trees while in the forest.

Female chimps Surprise (above) and Mini (below) climb a tree in the sanctuary. Incidentally, Surprise was unexpectedly born in the sanctuary despite the fact that all female chimps are on contraception to prevent them from conceiving because space and resources are limited. As in humans, contraception does not work 100% of the time.

Male chimp, Baron, is photographed with his “security blanket” –a rag he found in the forest at the Ngamba Island Chimpanzee Sanctuary. As a baby, he was taken from his mother and kept in a wooden cage for a year along with a sibling who died.

Female chimp, Medina, reaches out a hand requesting food. The hand reaching gesture among chimps is also used to beg for support from a friend or as a reconciliatory gesture after fights.

Caregivers feed chimpanzees at the Ngamba Island Chimpanzee Sanctuary. While the chimps forage for food in the forest during the day, their food is also supplemented by the sanctuary since the island’s natural resources are not enough to feed such a large population of chimps.

Six year-old chimp, Sara, stares at the reflection of herself in my camera’s lens. Sara was the island’s youngest chimp until the recent unexpected birth of an infant on March 27th of this year. She was confiscated from a trader in Southern Sudan and at the time of her arrival, was in bad condition. She has since become one of the sweetest and most beloved chimps on the island and is very expressive and playful.

Female chimp, Medina, scrunches up her face as she tries to catch a piece of carrot in her mouth. When Medina arrived at Ngamba Island, her canine teeth had been removed and her front teeth smashed. She was malnourished with a bloated stomach and was believed to have worms. She was treated and recovered steadily and now is a friendly and generous chimp.

Chimpanzees voluntarily file into their enclosure through a corridor to eat their evening meal after spending the day in the forest. Afterwards they sleep in enclosures where they use straw to make a bed on their own personal hammocks.

Female chimp, Medina, eats her evening meal of porridge in one of the chimp enclosures at the end of the day. I found myself completely fascinated with chimpanzee hands which are so much like our own.

Chimps enjoy their evening meal of porridge in one of the enclosures at the end of the day. While the chimps forage for food all day in the forest, their food is supplemented with fruit and vegetables at the sanctuary’s feeding station during the day and with porridge in the evening.

A chimpanzee reaches to take some cabbage from one of the caregivers at the end of the day after returning from the forest. Because chimps can be very aggressive, the sanctuary’s safety precautions include bars on the enclosures and a fence between the forest and the human camp.

Caregiver, Joseph Masereka, washes the outside of the chimp enclosures after the chimps have left for the forest for the day.

Male chimp, Kalema, is photographed at the edge of the island’s forest. Kalema is a happy and playful chimp. Athough he is one of the bigger chimps, he doesn’t enjoy the rough and tumble play of the older males. He can be quite shy and is often seen sitting and observing the activity around him from a distance.

A small group of chimps communicate with each other at the forest’s edge. While chimps don’t use language per se, they communicate with one another through a complex system of vocalizations, facial expressions, body postures and gestures.

Kalema eats the leaves off a plant at the sanctuary. Like humans, chimps eat a variety of vegetables, leaves, fruit and animal protein. As Jane Goodall discovered during her well-known study of chimps in the 1960’s, chimps also use tools such as stones to crack nuts, twigs to probe for honey or ants and even spears to hunt small animals!

Male chimp, Rambo, scratches his chin. Chimp gestures and facial expressions are, unsurprisingly, so similar to humans’.

Female infant chimp, Sara, is carried by caregivers after being sedated so Ngamba’s veterinarian, Dr Joshua Rukundo, could examine and treat pox in her mouth at the sanctuary’s clinic.

Ngamba’s veterinarian, Dr Joshua Rukundo, examines female infant, Sara, after caregivers noticed she had pox in her mouth that needed to be treated.

Six year-old Sara, is photographed with her mouth slightly open which is how caregivers first noticed the pox in her mouth. Sara was the island’s youngest chimp until the recent unexpected birth of an infant on March 27th of this year. She was confiscated from a trader in Southern Sudan and at the time of her arrival, was in a bad condition. She has since become one of the sweetest and most beloved chimps on the island and is very expressive and playful.

new work from my Rwandan students

Posted on February 18, 2015

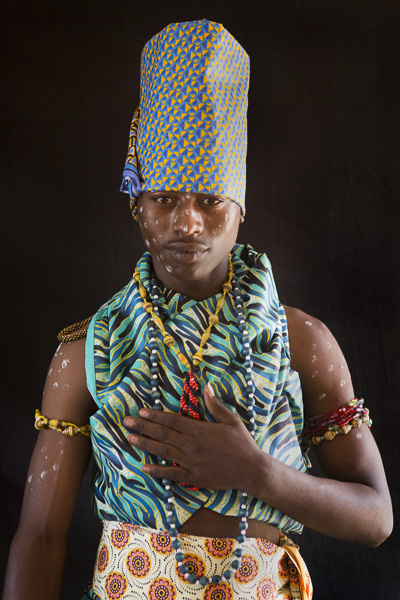

Portrait by Odila Umuziranenge. Orphaned at a young age, Odila has been participating in “Through the Eyes of Hope” for over seven years. She now runs the studio most afternoons and attends university classes in the evenings. When I first saw this portrait she created last week, I was stunned by the beauty and solemnity of it. Odila’s photographic progress only affirmed my decision to come back to teach in Rwanda again this year.

After my experience last year teaching photography to students at the “Through the Eyes of Hope” program in Kigali, Rwanda, I knew without a doubt that I had to come back. For those of you who didn’t see my blog post last year, here’s a bit of back story. “Through the Eyes of Hope” was founded by photojournalist, Linda Smith, in 2006 and is wonderful program that seeks to empower kids through photography. The program not only enables them to express themselves creatively but also means they can earn a bit of money through the studio they run where they primarily provide passport photos for locals. The students’ work has been shown in exhibits in both Rwanda and the US.

After I left Rwanda last year, I was determined to get more cameras for the kids to use since they were sharing three consumer-level cameras. I approached fellow professional photographers as well as local Cape Cod camera shop, Orleans Camera, about donating older generation cameras that they no longer used. I was so touched by the generous response I received and was thrilled to be able to send six professional-level digital SLRs with lenses and cf cards back to Rwanda.

What drew me back to Rwanda after last year’s experience was the kids’ enthusiasm, appreciation, exploding creativity and complete lack of entitlement. When I arrived at the airport three weeks ago, I was joyfully greeted by four of my students and received big, welcoming hugs. Since arriving, I’ve been training the students on the donated cameras, pushing them to improve their technical skills and also working on capturing “moments”. Since there are few photo studios in Kigali, we’ve especially been focused on improving their studio skills since they’re in unique position to offer professional studio photos to clients at a reasonable price. Together we worked towards preparing for an “open studio” day which we decided to make on Valentine’s Day, during which we would offer community members a free photo session and print. The idea behind this was to show the community the amazing work the students can do, create some positive PR for the studio and hopefully create some future customers.

During the days before Valentine’s day, the students had several assignments to create interesting studio portraits. I was thrilled with how enthusiastically they approached this task and what beautiful work came out of these assignments, some of which you will see below. When Valentine’s day arrived, I knew they were ready. Word spread quickly about what we were offering and we soon had a steady flow of community members coming in for the photo session and print. I was so happy and moved to see the customers’ consistently smiling responses when we handed them the glossy 4×6 print. Of course I was also elated to see what good work the students were producing, some of which is included below.

Beyond working together on their photography skills, we also made several field trips. The first was to Nyamata Church, a genocide memorial site where 10,000 Rwandans were brutally murdered during Rwanda’s 1994 genocide. Only seven people survived the attacks at Nyamata and these were all children who went unnoticed because they were hidden under adult bodies. None of the students had ever visited the site before. While they’ve grown up learning about the genocide at school, I thought seeing the memorial site in person would be powerful for them as well as for me and open up a dialog about Rwanda’s painful past. It did turn out to be a very difficult but meaningful experience for us all which I don’t really think words can describe.

Then, last weekend, some of the students joined me for a trip to Akagera National Park about two and a half hours from Kigali which again, most of them had never visited. Having grown up in South Africa myself, visiting the wilderness and seeing South Africa’s incredible wildlife was such a rich part of my childhood and it pained me to think that these Rwandan students had never seen the rich wildlife in their own country. It was wonderful to see their excited reaction to zebras, giraffes, hippos, a crocodile and the many other amazing wild animals we saw during our visit.

As my time with the students winds down, I think of all the moments in which I’ve been moved by my experience here. One particular moment that struck me most powerfully was during our drive to Nyamata to visit the genocide memorial site. The students are all passionate about music and they spent much of the drive singing together–primarily Rwandan religious songs–harmonizing beautifully and just having so much fun. As their voices rose up in the car, I found myself with a huge smile on my face coupled with a painful lump in my throat. How strange and beautiful to be driving towards this reminder of Rwanda’s traumatic past with a new generation joyfully singing their hearts out.

Portrait by Lucky Fikiri. This is a portrait of a community member who happened to be passing by the studio and came in to get her photo taken. Her shy but delighted response to seeing the print of herself was quite touching.

Self-portrait by Joshua Munyaburanga. Joshua calls this image “Two Brothers” as the boy on the right side of the frame is actually his brother, Sustain, while the face in the mirror is his own.

Portrait of fellow TEOH student, Lucky Fikiri, by Bobo Simubara. This photo came out of an assignment to create an imaginative studio portrait. The students got incredibly creative and while I was distracted editing work with another student, used fabric, jewelry, paint and other accessories to create images that reflected their culture.

Portrait of three brothers by Joseph Korerimana. These brothers were just a few of the community members who visited the studio on Valentine’s day to get a free photo and print of themselves. Many of them people who walked away with a print do not have any other print of themselves so it was wonderful to see their reaction to the glossy 4x6s they received.

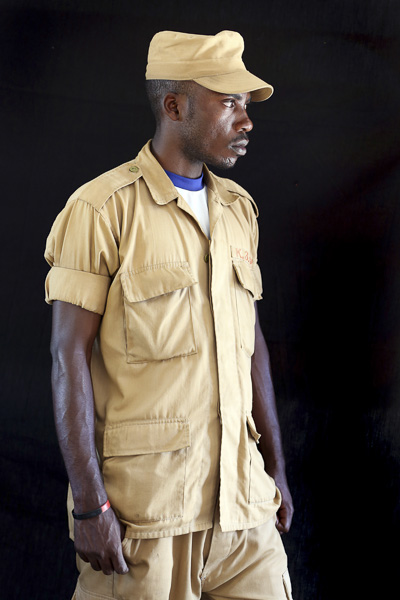

Portrait by Sustain Kabalisa. This security guard was one of the community members to visit the studio on Valentine’s day. I was struck by the beautiful light in this image and the seriousness of his pose.

Portrait by Joseph Korerimana. This is a portrait of TEOH student, Odila Umuziranenge and a friend’s child. Odila is one of TEOH’s original students and has really thrived over the years. I loved the joyfulness and spontaneity of this image and was particularly impressed since Joseph, the photographer, is one of TEOH’s youngest students and is in the early stages of learning photography.

Portrait by Justine Mukundiyukuri. This image came out of one of the portrait assignments I gave the students in preparation for our open studio event on Valentine’s Day. Again, I was impressed with Justine’s creativity in response to the assignment. Incidentally, the yellow container on the girl’s head is the kind of water container one sees children fetching water in all over Rwanda.

Portrait by Bobo Simubara. This image too emerged from the studio portrait assignments in preparation for our open studio event.

Portrait of fellow TEOH student, Sustain Kabalisa, by Hamis Ndikumukiza. Incidentally, the murals on the wall behind Sustain were painted by the students.

Portrait by Prossy Yohana. This image came out of assignment about depth of field. The students were learning how to use the donated SLR’s in manual mode and were asked to create portraits with a wide aperture which creates a shallow depth of field. I loved the pensiveness of this image and thought the shallow depth of field worked beautifully to isolate the girl against the background..

This image, made by Odilla Umuzirangenge, was one of my favorite to come out of an assignment the students were given to photograph at their church. The photo is of a choir member singing at the end of a three-plus hour pentacostal service (which I too attended with my student) held in a tent whose temperature rose and rose throughout the service. I thought this photo really captured the passion with which she approached her singing and praising.

Taken after our Valentine’s day open studio event, this is a photo of me with my “Through the Eyes of Hope” students and the equipment generously donated by my fellow photographers. Thank you again to all those who donated! I hope you enjoyed seeing what your generosity helped enable!

This blog strives to be an interesting place of discovery–a place to share beautiful or disturbing photos, discover new places and people and lose oneself in this extraordinary medium. If you or someone you know would like to receive new blog posts directly through your email, please sign up directly on my blog site–Apertures and Anecdotes (in the right hand column)–or email me at julia@juliacumesphoto.com. Thank you!

ps. comments are closed due to an overabundance of spam but please feel free to respond to this blog post directly if you have any questions or comments.

Journey to Machu Pichu

Posted on February 14, 2015

One of the many resident llamas is photographed at Machu Pichu, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and the most visited tourist destination in all of South America. Seemingly oblivious to the tourists trying to snap selfies with them, they wander about, occasionally stopping to take in the view between bites of lush Andean grass which they keep at a perfect length.

Nestled 7,000 feet above sea level in the Andes Mountains and almost entirely circled by the Urubamba River is a mysterious Incan city that up until just over 100 years ago, was completely unknown to the west. The story goes that in 1911 a Yale archeologist, Hiram Bingham, was searching for the lost city of Vilcabamba–the last Incan stronghold to fall to the Spanish–when a local farmer told him about some ruins located at the top of a nearby mountain. Bingham was then led by an 11 year-old boy to the site that has astounded archeologists ever since and also ignited a custody dispute that went on for almost 100 years, catalyzed partly by the fact that Bingham took artifacts from the site back to Yale for further study. What was particularly remarkable about the site was that the Incans had managed to keep it a secret from the Spanish for over almost 500 years and as a result, it remained relatively intact–a true icon of Incan civilization, architecture and engineering. Of course I’m referring to the now famous archeological site of Machu Pichu, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and the most visited tourist destination in all of South America.

During a visit to Peru last month, Machu Pichu was, unsurprisingly, on the top of our list of things to do. The journey to Machu Pichu itself is worth mentioning–the usual planes, trains and automobiles, then long snaking lines to buy tickets in the rain at the “Ministry of Culture” in the launching city of Cusco, more lines to buy bus and train tickets at a local tourist agency, another bus ride, a beautiful train ride through the Andes, a fairly intense but exquisite 2 hour hike up steep and mossy Andean steps from the town of Agua Calientes (for those who don’t want to hike, there are buses that take you directly to the entrance) and then the final ascent into the site itself which, at over 7,000ft with high altitude oxygen levels, is not made for the average couch potato. Or, for the really ambitious, one can hike the extraordinary 4-5-day Inca trail which passes through cloud forest, alpine tundra, tunnels and many Incan ruins. Despite the intense journey and the enormous number of tourists exploring the site–most with selfie sticks extended in front of their faces–I, like Hiram Bingham, could not help but be astounded by my first glimpse of the sublime city. Shrouded in clouds, and punctuated by the intense green grass and vegetation of the wet Andes, the stone city seems to have been created with a unique aesthetic sensibility, functionality and awareness of the surrounding environment. If, as archeologists now theorize, it served as a sort of retreat and ceremonial site for Incan rulers, it’s clear these men knew how to retreat and ceremonialize in profoundly thought-out style. In short, Machu Pichu is truly as beautiful and otherworldly as the guide books proclaim (albeit with way too many humans and selfie sticks).

Separated into three areas–urban, religious and agricultural, the structures are so perfectly matched with their surroundings. While the agricultural areas, with their well-defined terraces and aqueducts, make use of the natural slopes and the urban areas–which housed farmers, servants, teachers and the like–are built in the lower regions, the religious areas are located at the top of the city, with soulful and inspiring views of the beautiful Urubamba Valley far below. Perhaps one of the things that surprised me most was the fact that even though many of the stone blocks that make up Machu Pichu are massive–perhaps 50 tons or more–they are precisely cut (or sculpted?) and fit together almost perfectly without cement or mortar. Also, I was amazed at being able to imagine so well what life must have been like in this high altitude world. For instance, the many houses have stone shelves for displaying objects, high windows to allow enough light to enter at sunset and sundown and notches next to open stone doorways so that residents could lock their doors! There are baths and storage rooms, temples and of course the well-laid out terraces extensive enough to grow more than enough food for Machu Pichu’s residents. For a place that appears to be of another world, its details betray a city very much made for humans.

Of course there is so much more to be said about Machu Pichu’s intricacies–its Inti Watana, the Temple of the Sun, the Room of the Three Windows and the Terrace of the Ceremonial Rock but perhaps these places are best left to be explored in person. These days, besides the overabundance of tourists (whose free-wheeling explorations of the stone structures have put the Machu Pichu on the endangered archeological site list), there are also, surprisingly enough, a herd of free-range llamas whose heads occasionally pop up between the granite stones. Seemingly oblivious to the tourists trying to snap selfies with them, they wander about, occasionally stopping to take in the view between bites of lush Andean grass which they keep at a perfect length. They are, perhaps the only truly consistent and natural residents of the site and their peaceful presence and lovely dromedary-like faces amidst the beautiful ruins are what I held onto as we hiked back down the mountain.

Isolated in the Andean mountain range, the only way to get to Machu Pichu is by rail to Agua Calientes, the small touristy town at the base of Machu Pichu. The train ride itself is wonderfully scenic and the train’s large windows on the sides and ceilings make for a visually breathtaking experience.

To get to the site from Agua Calientes, one can either wait in long lines for the buses that snake up the mountain every 15 mins or one can hike up the steep Andean stairs for about two hours. The hike up was peaceful with some stunning views of the shrouded Andean mountains.

I, like Hiram Bingham, could not help but be astounded by my first glimpse of the sublime city. Shrouded in clouds, and punctuated by the intense green grass and vegetation of the wet Andes, the stone city is truly as otherwordly as the the guidebooks proclaim.

Visitors explore Machu Pichu’s stone structure. The number of daily tourists who visit the site relatively unresricted has put Machu Pichu on the list of endangered archeological sites and the Peruvian government is considering tighter restrictions.

Perhaps one of the things that surprised me most was the fact that even though many of the stone blocks that make up Machu Pichu’s structures are massive–perhaps 50 tons or more–they are precisely cut (or sculpted?) and fit together almost perfectly without cement or mortar. These stones were of course cut long before the invention of machinery.

A view of the sun temple from above. Apparently the sun temple was dedicated to the solar god and patron Incan deity, Inti. The temple was an important observatory in which the measurement of the solstices was undertaken. Underneath the Sun Temple is a cave-like room named the Royal Tomb in which the nobles and possible the Sapa Inca, ruler of the Cusco Empire and later the Inca Empire, were laid to rest in their mummified state.

Visitors explore the “urban” or residential areas of Machu Pichu which are built in the lower regions of the city and housed farmers, servants and teachers etc.

Machu Pichu is surrounded on three sides by the Urubamba River with cliffs dropping vertically almost 1,500 ft. The Urubamba accounts for the morning mists which rise up from its waters.

A view of the Inca Bridge which is part of a trail that heads west out of Machu Pichu. To prevent outsiders from entering Machu Pichu on this trail, a 20-foot gap was left in this section of the carved cliff edge over a sheer drop. Two tree trunks could be used the bridge the gap which was otherwise impassable.

The Incans were known for their use of agricultural terracing and Machu Pichu’s extensive stone terraces are a prime example of this practice. Terraces created larger areas for growing crops and allowed use of the more intense and longer sunlight exposure on the mountain sides during the day. Terracing also prevented soil erosion, mudslides and flooding and allowed farmers to better control the amount of water that fed the crops.

Visitors look ouf of Machu Pichu’s trapezoidal windows at the breathtaking view of the Andes. Because Machu Pichu was built between two fault lines, the Incans took great pains to build it to withstand earthquakes. Trapezoidal doors and windows which tilt inward from bottom to top was one of the features used to make the buildings more earthquake-proof.

This blog aims to be an interesting place of discovery–a place to share beautiful or disturbing photos, discover new places and people and lose oneself in this extraordinary medium. If you or someone you know would like to receive new blog posts directly through your email, please sign up directly on my blog site–Apertures and Anecdotes (in the right hand column)–or email me at julia@juliacumesphoto.com. Thank you!

ps. comments are closed due to an overabundance of spam but please feel free to respond to this blog post directly if you have any questions or comments.

a dog’s life–Peru

Posted on January 17, 2015

A Peruvian hairless dog stops to observe a train arriving in Agua Calientes, a town at the base of Machu Pichu. I saw many of these ancient Peruvian dogs walking around in Agua Calientes with specially-made t-shirts. Temperatures in this area are cool in the mornings and evenings. This was just one of many moments in my travels through Peru in which I noticed how much Peruvians embrace their canine residents.

As a dog-lover, I always notice dogs and their general well-being when I travel. In many countries, I’ve learned that dogs are seen less as family members than as security guards. Frequently, they’re kept on short chains or slinking around the shadows of the family’s back yard, nervous and ready to snap at the smallest infraction. Alternatively, they are street dogs riddled with ticks or infections, mangy or so thin one can count each rib from a distance. Often, in these same countries, dogs are perceived as dirty (which they usually are because of lack of care) and people balk at the idea of petting a dog or taking him into one’s home. I know that poverty plays a significant role in how cultures treat their dogs. When there isn’t enough food for humans, it’s understandable that dogs too will go hungry.

So happily, one of the first things I noticed in Peru was that dogs are ever-present, well-fed and Peruvians seem to love them! Every corner I turned–whether on the streets of Lima or the tiny towns of the Sacred Valley or Colca Canyon–I joyfully witnessed a new vignette of canine bliss. I saw dogs being scratched, cuddled, played with, fed with market scraps, or simply allowed to sleep peacefully, curled up close to human companions. While I noticed few collars and rarely a leash on these Peruvian dogs and they seemed to wander the streets peacefully with a traffic savviness my own pooches certainly will never attain, they did not seem to be strays or gather in packs as street dogs sometimes do. They simply looked like there were going about their days, exploring the usual nooks and crannies, visiting their doggy or human friends and then wandering home at the end of the day for a good meal.

Who knows why dogs are so integrated into Peruvian culture in a way they aren’t in so many other countries. I know that the Peruvian hairless dog breed dates back to pre-Incan times but whatever the reason, I was so inspired by this canine-loving culture that I thought I’d share some of my favorite Peruvian doggy moments.

I watched this young boy play with his dog for a long time outside his family's store in Maca. I was struck by the affection and trust between them.

A young woman texts on her phone while waiting for customers at a tourist shop in Cuzco. I was touched by the little bed her dog slept on and the way in which she draped her arm around him as he slept.

A dog snoozes peacefully in Lima's Plaza de Armas close to the Government Palace, seemingly unconcerned about the presence of riot police beside him.

A dog sleeps on the step of his family's home in Pisac. I saw dogs sleeping in so many spots like this.

Three young girls play with a puppy on the steps outside their family's restaurant in Agua Calientes--the town at the base of Machu Pichu.

A dog seemingly enjoys being in the midst of the action on a street corner in Pisac. While he was clearly blocking the sidewalk, I didn't see anyone chase him away.

A boy and his dog keep each other company in the entranceway of the family's convenience store in Pisac.

A little girl nonchalantly rests her foot on a dog's head as she hangs out with her friend in Chivay. I was surprised by how tolerant the dog was of the little girl's foot.

A dog crosses the street at the cross walk while another walks down the center of the street in the tiny town of Chivay.

A woman affectionately touches the nose of her dog while waiting for tourists to purchase her wares at the Incan historical site of Q'enqo just outside of Cuzco.

If you or someone you know would like to receive new blog posts directly through your email, please sign up in the right hand column or email me at julia@juliacumesphoto.com. Thank you!

ps. comments are closed due to an overabundance of spam but please feel free to respond to this blog post directly if you have any questions or comments.

Into the Amazon…

Posted on January 11, 2015

I photographed this beautiful juvenile tree boa while on a night walk through the Amazon jungle in southeastern Peru.

The Amazon jungle has always inhabited a special place in my imagination. Mysterious, faraway, full of ominous and beautiful creatures, it seemed out of the range of possibility to actually experience it. Which is why it was all the more extraordinary to find myself motoring up the Tambopata River–a tributary of the Amazon river in southeastern Peru–on a small wooden boat heading into the Amazon basin for four days earlier this week.

The air engulfed me like a hot, wet blanket when I first walked out of the airport in the Amazonian town of Puerto Maldonado and I was surprised to see how sunny it was given that this time of year it can rain for days without stopping. My second surprise came a few hours into our boat ride when we came upon a small creature swimming across the river. At first I thought it was just another log like the many we’d passed close to shore and then I saw it had eyes, a mouth and a very determined expression. Our guide, Jair Mariche, excitedly exclaimed it was a three-toed sloth and told us that in all his years of guiding, he’d only seen a sloth once and certainly not one swimming. This was only the first of a series of extremely lucky sightings we had during our four days of exploring the Amazon.

The days that followed were full of extraordinary (and very muddy and sometimes wet) adventures during which we saw numerous snakes, spiders (including a family of tarantulas), wild pigs, giant river otters, monkeys, macaws, an electric eel, a wide variety of frogs, extraordinary selection of insects and birds and of course, vegetation that grows on a scale I struggled to wrap my mind around. At the end of each day, I was struck by how much my fantasy of the Amazon felt accurate. I couldn’t seem to get enough of the fact that the wildlife in the Amazon operates independently of human existence, that each creature seems to have found a unique niche to inhabit and thrive in and that all the Amazon’s creatures represent endless adaptations that have allowed them to survive in their complex and competitive world.

A rainstorm looms in the distance as we motor up the Tambopata River in a narrow wooden boat into the Amazon basin.

A three-toed sloth swims across the Tambopata River. Despite the fact that they move very slowly in trees, the three-toed sloths are surprisingly agile swimmers.

Trees in the Amazon compete for light and there are, as result, a lot of extremely tall trees. Some trees reach heights of over 420 feet!

An owl butterfly--known for the large eye-spot patterns on its wings that resemble owl eyes--rests on a tree.

Red and green macaws gather on a clay lick along the Tambopata river. There are numerous theories as to why the birds consume the clay on an almost daily basis in the Amazon. One theory is that some foods eaten by macaws in the wild contain toxic substances which the clay they eat neutralizes.

A pair of scarlet macaws fly off after visiting a clay lick. Macaws mate for life and are almost always seen flying with their mated pair.

A capybara, the largest rodent in the world, forages for food on the banks of the Tambopata River. The rodent, which is related to the guinea pig, hangs out in groups of 20 or more animals. While it isn't endangered, the capybara is hunted for its meat, its hide and also for a grease from its thick fatty skin which is used in the pharmaceutical industry.